School Innovation: VR Headsets or a Cardboard Box?

School innovation requires educational leaders to shift the narrative surrounding technology away from devices towards future-focused skills and dispositions which can be developed through approaches to teaching and learning.

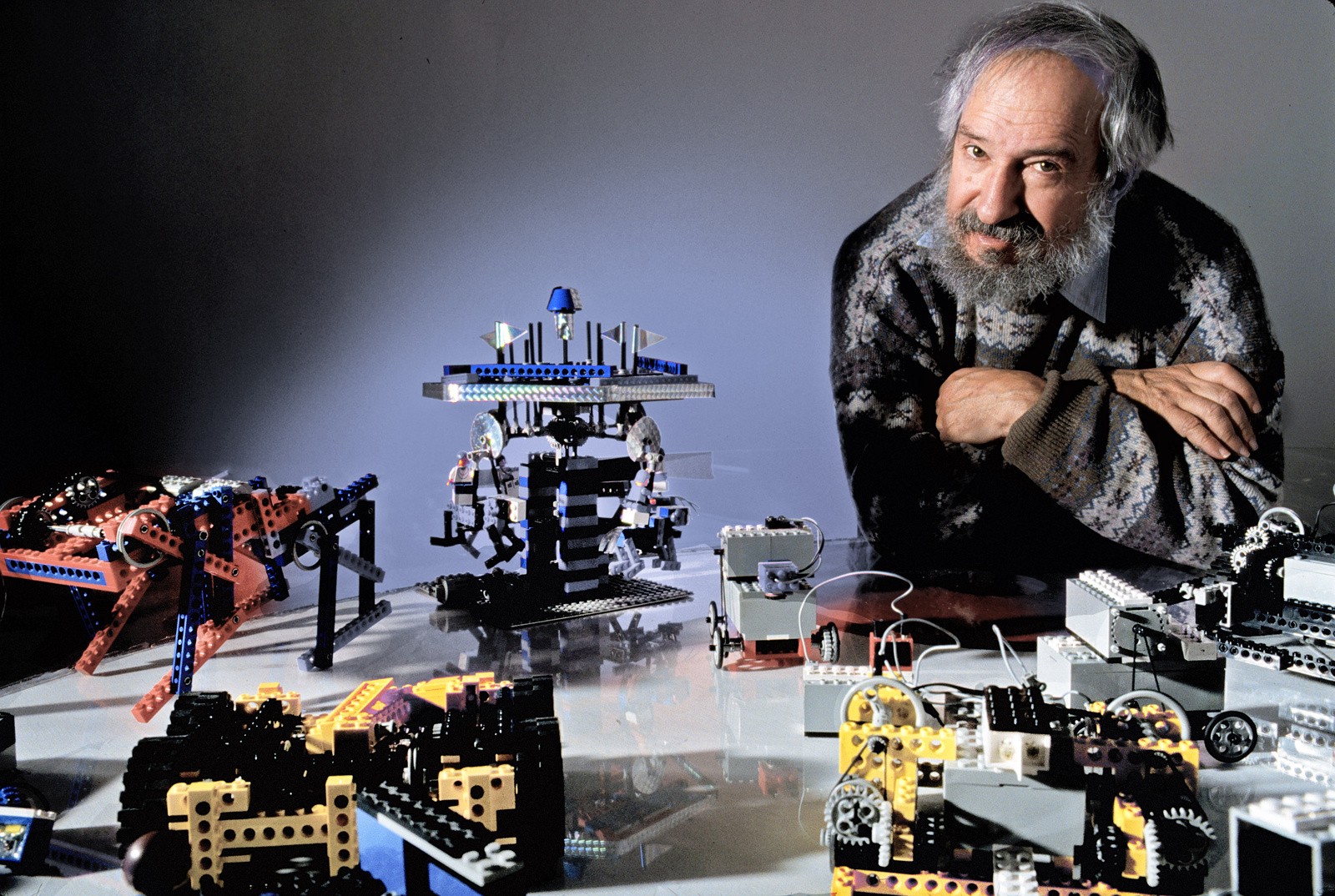

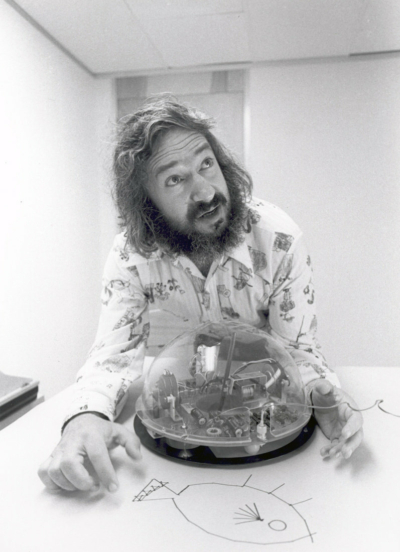

Which of the following devices is the most innovative for schools: a laptop, a tablet, a VR headset or a cardboard box? Seymour Papert, a mathematician and computer scientist who spent most of his 40 year career researching and teaching at MIT, was one of the pioneers of artificial intelligence as well as the constructionist movement which posits that children learn best when creating models as they encourage learners to make connections between different ideas and bodies of knowledge. He believed that computers, programming and even the modest cardboard box could be capable of supporting personal and powerful ways of thinking in the digital age – if used appropriately.

Changing Skills and Dispositions

One of the many future challenges facing our young people will be tectonic change in the way we work, not least in the way that emerging technologies will affect the nature of – and need for – many of the careers for which schools have traditionally prepared their students. Instead, a focus on active learning, creativity, collaboration and complex problem-solving are vital for stimulating innovative ideas and leveraging new technologies. Cognitive flexibility and emotional intelligence are also important in ensuring young people have the skills to adapt to changing landscapes.

However, the way many school leaders communicate and make decisions around technology is with a focus on specific devices and software. Much of the discussion surrounding technology in schools tends to be on the latest laptops, 3D printers, VR headsets or automated platforms as evidence of innovation. What if instead educators focused on technology as a method by which to encourage future skills and dispositions?

Instructionism and Constructionism

Such skills and dispositions need not be taught explicitly, but can be embedded in the curriculum through a shift from instructionist to constructionist approaches to teaching and learning. Papert advocated that the role of the teacher should be to create the conditions for invention rather than provide ready-made information – a premise that is beginning to be realised through the rise of pupil-centred approaches in schools around the world.

High Tech High, a network of charter schools in California opened as ‘technology-focused’ schools in 2000, but over a twenty year journey has discovered that encouraging pupils to construct knowledge and understanding through project-based learning is a more effective way to prepare them for a tech-enabled world. Their learning projects are now guided by four connected principles: equity, personalisation, authentic work and collaborative design.

In Canada, the province of Ontario recently refreshed its curriculum not by altering subject content, but by requiring teachers to embed, and report on, transferable skills such as critical thinking, creativity and innovation, problem-solving, and citizenship within learning experiences that are cross-curricular and theme-based.

Finland has moved completely away from subject silos towards topical learning, with what they referred to as ‘phenomenon-based learning’ which aims to support pupil agency and a holistic approach to real-world projects.

The International Baccalaureate curriculum and its inquiry-based approach to learning has also become a popular method in which to develop competencies such as creative and collaborative thinking, media and information literacy and reflective skills in learning units driven by interdisciplinary concepts.

In the U.K. context, one way in which The Girls Day School Trust is exploring the development of future-focused skills is by applying a Design Thinking approach to the curriculum to facilitate academically rigorous and cross-curricular projects that encourage problem-solving and content creation. It is a way of working that seeks to unveil the real-world applications of information by presenting content as problems to be solved and framing it in a way that is authentic for students.

Such approaches are not a radical move away from the acquisition of content knowledge, which continues to be an important part of the learning process, but rather a shift in focus from acquiring and transmitting information towards applying such knowledge in new and meaningful ways. It’s not just what is taught, but how it is taught, that matters in schools today.

Providing Opportunities for Construction

Let’s take for example teaching Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in an English class. Traditionally, a teacher may design a syllabus of activities for pupils to learn about the content of the play and deconstruct the rhetoric employed by the political figures. Although technology could be utilised to digitise resources, run automated quizzes and facilitate collaborative writing tasks, there is little motivation to embed technology in the learning process as the end goal – a handwritten essay – does not require technology. Employing a constructionist approach may instead refocus the purpose of the text as stimulus for pupils to engage with contemporary political messages through the creation of their own media products.

Pupils could create mashup videos comparing how the characters in the play and current political figures use language to villainise their opponents. They could further create a reaction video to a peer’s work with a corresponding transcript that is appropriately cited – a meta-analysis in disguise. Or upload the videos to a class video channel and examine the analytic data to discover what holds viewers’ attention.

Pupils could further connect with a class in another country to discuss political figures and media messaging they experience, to gain perspective and cultural insights. Or test their own media creations on a different audience.

What if the purpose of technology was not to automate and digitise teacher-directed learning methods, but to provide opportunities for students to explore, discuss, test and design solutions to authentic problems?

Would pupils be able to apply knowledge in more original and meaningful ways on standardised assessments?

Would they be better equipped for life after school?

Pedagogy, Not Technology

In his book The Children’s Machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer Papert observes: “Nothing could be more absurd than an experiment in which computers are placed in a classroom where nothing else has changed” (1993, p. 149). The quantity and quality of devices is not a direct correlation to a school’s ability to prepare pupils to be leaders in the digital age. Instead, the success of a school’s technology programme relies heavily on school leaders’ ability to clearly communicate a purpose for technology use, as well as the encouragement for teachers to design instructional approaches that enable pupils to construct knowledge and develop the strategies, skills and attitudes to tackle complex problems.

So, could a cardboard box be just as innovative as VR headsets if pupils are using it to prototype solutions to real-world problems? How might schools shift the focus of technology away from devices, towards learning approaches that foster future-focused skills and dispositions?

Papert, S. (1993) The Children’s Machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer. Basic Books: New York.

Cris Turple provides digital strategy guidance and facilitates professional development opportunities for The Girls’ Day School Trust, a group of 25 all-girl independent and academy schools across the U.K. She previously worked in Canada, Hong Kong and Singapore as a classroom teacher, instructional technology coach and curriculum coordinator. Cris is an Apple Distinguished Educator, Google Certified Trainer and Innovator, and Microsoft Innovative Educator who holds a Masters Degree in Educational Technology from the University of British Columbia.

Connect with her on Twitter: @CrisTurple