Educational Technology, Workload and Teacher Retention

The importance of stakeholder engagement. By Vaughan Connolly (University of Cambridge) and Rachel Evans (Wimbledon High School)

Key Points

- Realising impact from ed-tech is key and requires effective stakeholder engagement.

- Stakeholder engagement helps build a culture of innovation and collaboration.

- 2,079 teachers from 149 English schools responded to the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (2018). Results show that perceptions of stakeholder engagement are linked to improved perceptions of workload and job satisfaction and teachers’ happiness with their school.

- These results suggest that undertaking fewer projects, to allow for greater stakeholder engagement, may lead to multiple benefits for ed-tech, workload and staff retention.

- Good stakeholder engagement connects with people’s feelings, views, beliefs, and values. It places learners’ needs at the heart of discussions and listens and understand teachers’ contexts. It forensically asks, “What will implementation look like in each classroom?”

- Workflow analysis can be used for effective stakeholder engagement.

When Less is More

With school budgets under large pressures, and a greater awareness of past disappointments arising from ed-tech initiatives, the advice of the Education Endowment Fund, is ever more important: “schools should probably make fewer but more strategic choices” (2018, p. 10). At a time of limited financial resources, fewer initiatives, done well, have obvious benefit. Key to success is spending sufficient time connecting with both the hearts and minds of colleagues and seeking to understand the values, core beliefs and feelings of those who will ensure that projects achieve the desired impacts for pupils’ learning (Cohen & Mehta, 2017; Robinson, 2017).

In highly successful change efforts, people find ways to help others see the problems or solutions in ways that influence emotions. Kotter and Cohen, 2012

While it may seem a luxury to spend more time undertaking stakeholder engagement, evidence from the OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey suggests that this one tool can help schools with workload and staff retention, as well as ensuring ed-tech achieves impact. So too, case studies of schools who have made a success of ed-tech, confirm these points. In this blog post, we first present the evidence from the TALIS survey, and then discuss how stakeholder engagement has worked, practically, in schools helping develop a culture of innovation and ed-tech impact.

Stakeholder engagement for successful implementation and staff retention

Winning the hearts and minds of those who must implement reform is consistently seen throughout studies of successful change programmes. Most recently, Professor Jal Mehta and Dr David Cohen, of Harvard and Michigan universities, have comprehensively studied educational reforms and concluded that in addition to effective infrastructure, training and support, it was also essential that those implementing reform perceive a real benefit to satisfy unmet learners’ needs (Cohen & Mehta, 2017). Understanding these needs and perceived benefits can be very much helped by extensive stakeholder engagement leading to clear goals, effective implementation planning, and strategy supported by all. With that in mind, it is concerning that 43% of England’s teachers in the TALIS 2013 survey did not agree that they were given opportunities to actively participate in school decision making.

Although TALIS 2018 shows stakeholder engagement rising since then, a 2018 survey by the Independent Schools’ Bursars’ Association (ISBA) reported the views of 406 bursars, 367 IT directors and the teaching staff of 315 schools (Phillips & Hodges, 2018), and found that 80% of teachers surveyed were unaware of the IT vision and strategy in their school, and that only 25% of schools report including their teachers in the development of their IT strategy. This may help explain further challenges raised by the ISBA survey: only one-third of bursars felt their IT expenditure was good value for money, two-thirds of academic deputy head-teachers lacked confidence in their teachers’ ability to use ICT, and teachers reported low take-up of new technology.

In studies of teacher retention stakeholder engagement is also important. In particular, the work environment and empathic and supportive leadership have been linked to staff intentions to move schools or leave the profession. In other fields even simple employee satisfaction surveys have been causally linked to reduced employee attrition and absenteeism (Adhvaryu, Molina, & Nyshadham, 2019). The message here is clear: stakeholder engagement is an easily accessible way for school leaders to build environments that better retain staff at the same time as insuring successful ed-tech implementation.

Teachers are “three times more likely to plan to transfer from schools with particularly poor conditions of work than are teachers whose work environment is of average quality (Johnson et al., 2012, p. 30).

Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018

England has participated in the OECD’s TALIS study in both 2013 and 2018, where lower secondary school teachers are asked about their views on their school, their approach to teaching, the profession and so on. Of key interest are questions relating to job satisfaction (e.g. ‘I would like to move school if I could’, ‘I would recommend my school as a good place to work’ and ‘I regret becoming a teacher’), workload stress (‘I have too much marking’, ‘I have too much planning’), and stakeholder engagement (‘My school provides staff/parents/students with ample opportunity to participate in decision making’, ‘staff take shared responsibility for …’). With an 80% response rate in England (2,079 teachers, 149 schools), this is a highly representative, valid and reliable survey.

Given the importance of stakeholder engagement in ed-tech projects, our research asked the question – how does teachers’ perceptions of stakeholder engagement impact on their perceptions of workload, job satisfaction and other related factors?

To answer this question, path analysis was conducted using Stata 16 and TALIS data publicly available via the OECD website. The data was checked to ensure it met necessary statistical preconditions and was then analysed using appropriate BRR weights.

What did TALIS 2018 tell us?

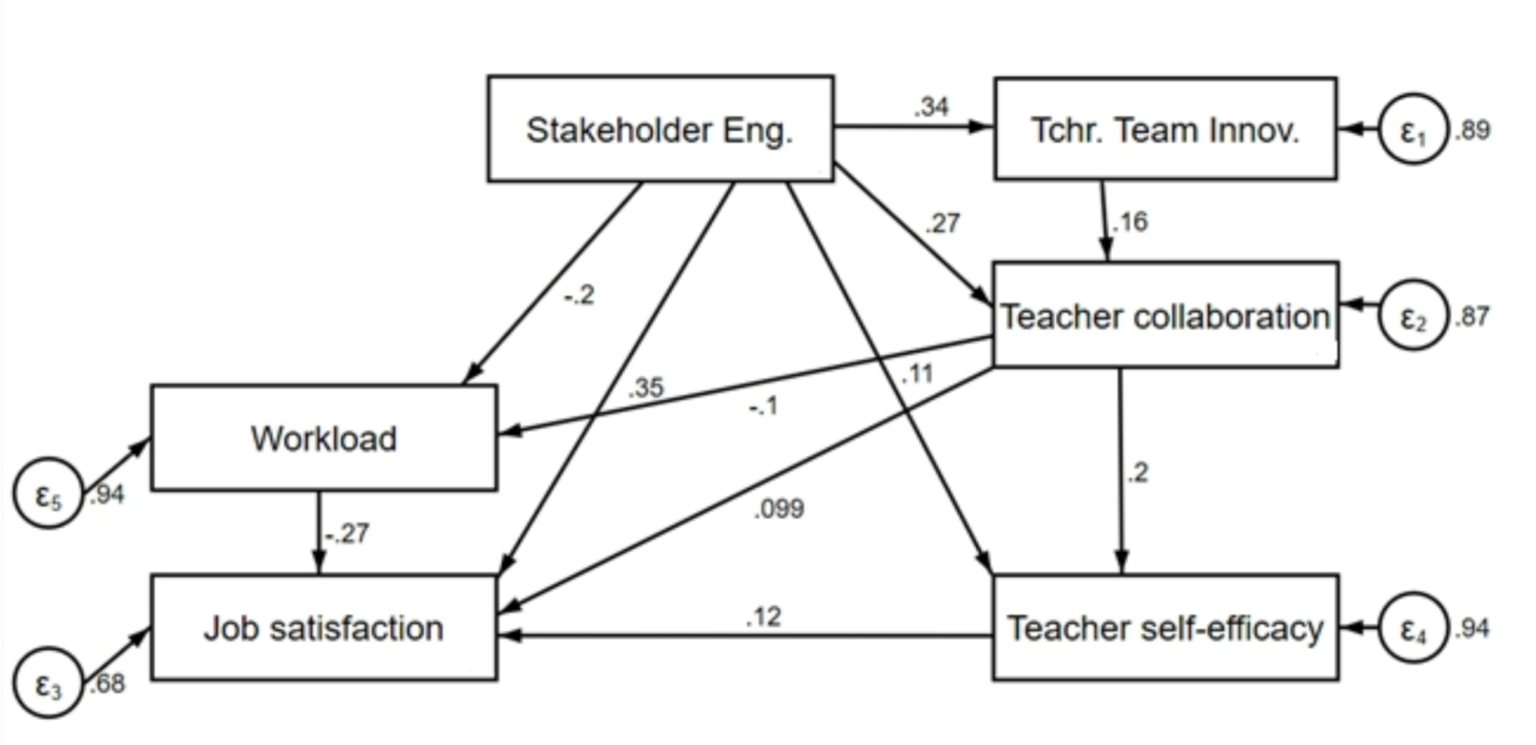

Stakeholder engagement is important. In this analysis, teachers’ perceptions of stakeholder engagement had almost twice the impact on teachers’ job satisfaction than did their perception of their workload. It also had large effects on perceptions of teacher collaboration, and team innovativeness – both key ingredients to teacher collective efficacy, John Hattie’s new number one effect for promoting student progress. The direct effects of stakeholder engagement can be seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Stakeholder Engagement and its theorised impact on Workload, Job Satisfaction, Collaboration and Efficacy (teachers, n=2,079 – standardised)

Figure 1 suggests that stakeholder engagement may benefit innovation, collaboration, teacher-self efficacy and job-satisfaction. All relationship shown are highly statistically significant (p=0.000). The overall model fit (unweighted) was very good ( 2 (4)=6.880 , p=0.142; RMSEA=0.021; CFI=0.999; TLI=0.991; SRMR=0.012) with an SRMR=0.017 when applying weights. While Figure 1 only shows the direct effects, Table 1 combines both direct and indirect effects to show that stakeholder engagement may offer many significant benefits to school leaders.

Table 1 – Standardised Model Results (direct and total effects)

| Links | Direct effects | Total effects (Direct and Indirect) |

|---|---|---|

| team innovativeness <– stakeholder engagement | .34*** | .34*** |

| teacher collaboration <– team innovativeness | .16*** | .16*** |

| teacher collaboration <– stakeholder engagement | .27*** | .33*** |

| job satisfaction <– team innovativeness | .02*** | |

| job satisfaction <– teacher collaboration | .10*** | .15*** |

| job satisfaction <– stakeholder engagement | .35*** | .46*** |

| job satisfaction <– self-efficacy | .12*** | .12*** |

| job satisfaction <– workload | -.27*** | -.27*** |

| self-efficacy <– team innovativeness | .03*** | |

| self-efficacy <– teacher collaboration | .20*** | .20*** |

| self-efficacy <– stakeholder engagement | .11*** | .17*** |

| workload <– team innovativeness | -.02*** | |

| workload <– teacher collaboration | -.10*** | -.10*** |

| workload <– stakeholder engagement | -.20*** | -.20*** |

*** significant at the 0.001 level

Thus, perceptions of stakeholder engagement have a highly significant positive relationship with perceptions of team innovativeness (0.34), job satisfaction (0.32), teacher collaboration (0.29), and teachers’ sense of self-efficacy; it has a negative direct impact on workload stress (-0.22). These standardised coefficients mean that a one standard deviation (SD) increase in stakeholder engagement is related to a 0.32 SD increase in job satisfaction and a 0.22 SD decrease in workload stress. It is also possible that teachers’ reports of workload stress are also mitigated by higher levels of teacher collaboration.

Does this match TALIS 2013?

TALIS 2013 was previously analysed by Sims (2019) who found teachers’ perceptions of leadership to be the most significant predictor of England’s lower secondary teachers movement intentions. In this analysis leadership was a composite term comprised of feedback for staff (0.33); employer support for CPD (0.4); staff engagement and participation in decision making (0.79); fostering a culture of shared responsibility (0.89) and mutual collaborative support (0.91); providing clear vision and direction (0.97); and support for teacher autonomy (0.33) (where these numbers indicate the relative importance of the reported elements of leadership). Again in 2013, as in 2018, stakeholder engagement appears an easy but effective option for school leaders.

What makes for good stakeholder engagement?

But what accounts for effective stakeholder engagement? Harvard professor John Kotter has long studied the process of institutional change and finds that stakeholder engagement that speaks to both ‘hearts and minds’ is vital and frequently overlooked (Kotter & Cohen, 2012). This mirrors Distinguished Professor Viviane Robinson’s research on leadership which found that successful change in schools is promoted when school leaders engage with colleagues’ unspoken but enacted values and theories about learners and teaching, which are not always the same as their espoused values and theories. One way to discuss this is suggested by Professor Helen Timperley, world expert on effective CPD, who finds extensive evidence that dialogue best starts with an analysis of learners, learning and the anticipated impact of ed- tech (Timperley, Wilson, Barrar, & Fung, 2008). A further opportunity for stakeholder engagement is offered by conducting workflow analysis, as we discuss next.

Workflow analysis for ed-tech projects

In order to achieve learning impact however, ed-tech must also survive the realities of the classroom. By this we mean the step-by-step moments, the how and when, in a very practical experiential way for teachers using ed-tech to benefit learners and learning. We call this workflow analysis and find, on the basis of action research in multiple ISC schools, that workload analysis provides a useful and necessary focus for stakeholder engagement. This asks project planners to engage with colleagues to fully detail the minutiae of what implementation will look like in the classroom. Not only can this help win the hearts and minds of those who are most essential to ensuring the success of ed-tech projects, but it also offers a surety that workload is not exacerbated by such projects. We offer two examples of this ‘workflow analysis’ in action:

Workflow Analysis (example one)

Shared, bookable device sets are a popular choice as a first step on the pathway towards 1:1 devices into the classroom or when budgetary constraints mean that 1:1 might not be possible. What we hear from bursars and digital leaders is that such class sets are often under-utilised and come with a raft of frustrations.

What are some of the practical challenges with this kind of project?

- The teacher needs to book the devices in advance – how will they do this? Will the devices be charged? How do you get them to the classroom? Any steps? Is there room in the classroom for the trolley?

- When in the classroom, how are they distributed/ collected at the end of the lesson. Do they have to be manually switched off when returning? What about students that just close the lid?

- Does every student plug their laptop back in the trolley or just place it on a shelf? Do they go back in numbered order?

- Is the app/program required already installed on them? If not, how does that get set up? Who does the teacher ask? Which department pays for it?

- Where do students save their work? How do they get the work off the device? How do they get the work to the teacher? If they had to log in, how does the teacher make sure they log out?

These apparently simple issues can so easily throw the project off track. These kind of frustrations may be at the root of some of the ‘lack of time’ reasons that teachers give for resisting new technology (Tallvid, 2016). Failure of the project leader to engage with this kind of detail can undermine confidence in the project and in teachers’ understanding of the value of the technology for learning.

Where these workflow problems are thought through carefully with staff in the classroom before a project begins this can act as a good opportunity for engagement about the project and ensure that staff have felt heard – in other words, letting teachers engage with the pedagogy by smoothing out the practical concerns.

Workflow Analysis (example two)

Another example of ed- tech implementation where workflow can make or break the project is the introduction of digital homework systems. There are many on offer – either standalone apps, integrated systems within a VLE, or ecosystems like Google Classroom or Microsoft Teams. Can they actually make homework more effective, feedback more formative and save teachers’ time? It depends on whether the project team have thoroughly assessed the workflow wins and losses in evaluating the package.

What are some of the workflow challenges of this kind of project?

- Where will the teacher prepare the work? Are they able to share resources they have already developed, or are they tied to working within the chosen app or ecosystem? If they can share existing resources, how do the students receive and interact with the content?

- Can teachers share the burden of preparing resources and assignments? Can they collaborate on individual homework tasks, and can then also pool resources they already have? Can they tweak existing resources for their own classes and groups to allow for their own professional angle on the subject matter, to reflect what happened in the lesson, or for differentiation?

- How will the students submit the work? Does text have to be written or typed into the app interface or can other documents or images be attached?

- How will the teacher mark the work? Will they see the whole classes submissions in one place? Do they need to download anything? Can they write or type directly onto the work?

- How will they award a mark or grade? Can any part of the process be automated.

- How will the student receive the feedback? Can they respond to it within the app? It is possible for the teacher to review work and add feedback before it is complete and submitted?

Where these challenges are carefully thought through before implementing a digital homework system, the outcomes can be excellent for both staff and students. For example, at Wimbledon High School almost all departments have now adopted Microsoft OneNote for classwork, distribution of resources to pupils and in many cases, for homework. Critical to the success of this has been the understanding of how to use the tool effectively. That understanding came from the project leaders listening to the experiences of a small group of pioneering staff who tried out the technology. Arising from this stakeholder engagement was a crucial time saving practice. Originally, early adopters asked students to submit work in a ‘homework’ section set up by teachers. However, this meant some students could not find their homework, and for work that was submitted to the correct location, teachers found marking to be onerous with multiple clicks required to switch between each student’s work. Instead if teachers used the distribute function instead, the whole process was simplified and the use was more effective:

- Teachers could send work to students with three clicks

- Work appeared for students in their own OneNote, rather than requiring them to go find it in a shared area.

- Students could more easily submit completed work in the right place which enabled the review function

- Using the review work function meant teachers could move from one student’s work to another with only one click.

- Using distribution means that all student pages are gathered together, making for an easy way of reviewing class progress at a glance.

The project has been through several iterations now and digital leaders continue to keep department practice under constant review to ensure that the system is being used in the best possible way.

By empowering groups of staff to conduct their own small scale trials, everyone stays on board and is able to drive onward with new and innovative uses which benefit student learning.

Summary

Stake holder engagement has the largest impact of the variables we analysed in TALIS for England’s lower secondary teachers. It is one of the easiest factors to implement but takes time and is a clear example of where less can be more. In a case of ‘five birds, one stone’, stakeholder engagement may benefit perceptions of workload, job satisfaction, team innovativeness, teacher collaboration and the success of ed-tech projects. Effective stakeholder engagement does take time however, and all too often shortcuts are taken which undermine success. Instead, invest in engagement with colleagues’ feelings, views, beliefs, and values and place learners’ needs at the heart of discussions. Similarly, an iterative process of workload analysis will also engage teachers on matters of key importance. It is crucial to listen and understand teachers’ contexts – what will implementation look like in their classrooms – for this is where success is cemented.

References

Adhvaryu, A., Molina, T., & Nyshadham, A. (2019). Expectations, Wage Hikes, and Worker Voice: Evidence from a Field Experiment (Working Paper No. 25866; p. 36). Retrieved from National Bureau of Economic Research: http://www.nber.org/papers/w25866

Cohen, D. K., & Mehta, J. D. (2017). Why Reform Sometimes Succeeds: Understanding the Conditions That Produce Reforms That Last. American Educational Research Journal, 54(4), 644–690. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831217700078

Education Endowment Foundation. (2018). Putting Evidence to Work: A School’s Guide to Implementation. Guidance Report. Retrieved from https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Publications/Implementation/EEF-Implementation-Guidance-Report.pdf

Kotter, J. P., & Cohen, D. S. (2012). Heart of Change: Real-Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business Review Press.

Phillips, I., & Hodges, A. (2018, May 10). ISBA IT Survey 2018. Presented at the Independent Schools Bursars’ Association Conference. Retrieved from https://iscdigital.co.uk/a-bursars-it-six-pack/

Robinson, V. M. J. (2017). Reduce Change to Increase Improvement (First edition). Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin.

Sims, S. (2019). Modelling the relationships between teacher working conditions, job satisfaction and desire to move schools. British Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3578

Tallvid, M. (2016). Understanding teachers’ reluctance to the pedagogical use of ICT in the 1:1 classroom. Education and Information Technologies, 21(3), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-014-9335-7

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2008). Teacher professional learning and development. Retrieved from http://www.orientation94.org/uploaded/MakalatPdf/Manchurat/EdPractices_18.pdf

Appendix A

Items (and standardised factor loadings) for scales

Based on a comprehensive conceptual framework, the OCED converted individual questions into a range of scales which all exhibited good reliability and validity. The following list the items used to construct scales used in this paper, alongside their factor loadings for lower-secondary teachers, England. Two scales are composite scales.

Stakeholder engagement

| 48. | How strongly do you agree or disagree with these statements, as applied to this school? (Responses from: “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (4)) | Std.Factor Loading (Eng) |

|---|---|---|

| A | This school provides staff with opportunities to actively participate in school decisions. | 0.845 |

| B | This school provides parents or guardians with opportunities to actively participate in school decisions. | 0.714 |

| C | This school provides students with opportunities to actively participate in school decisions. | 0.754 |

| D | This school has a culture of shared responsibility for school issues. | 0.736 |

| E | There is a collaborative school culture which is characterised by mutual support. | 0.656 |

Workload Stress

| 52. | Thinking about your job at this school, to what extent are the following sources of stress in your work? Response options: “Not at all” (1), “To some extent” (2), “Quite a bit” (3), “A lot” (4). | Std.Factor Loading (Eng) |

|---|---|---|

| A. | Having too much lesson preparation | 0.692 |

| B. | Having too many lessons to teach | 0.699 |

| C. | Having too much marking | 0.708 |

| D. | Having too much administrative work to do (e.g. filling out forms) | 0.515 |

| E. | Having extra duties due to absent teachers | 0.350 |

Team Innovativeness

| 32. | “Thinking about the teachers in this school, how strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?” (Responses from: “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (4)) | Std.Factor Loading (Eng) |

|---|---|---|

| A. | Most teachers in this school strive to develop new ideas for teaching and learning. | 0.783 |

| B. | Most teachers in this school are open to change. | 0.827 |

| C. | Most teachers in this school search for new ways to solve problems. | 0.845 |

| D. | Most teachers in this school provide practical support to each other for the application of new ideas | 0.716 |

Job Satisfaction = Job satisfaction with work environment + Job satisfaction with profession

| 53. | We would like to know how you generally feel about your job. How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements? Response options: “Strongly disagree” (1), “Disagree” (2), “Agree” (3), “Strongly agree” (4). | Std.Factor Loading (Eng) |

|---|---|---|

| Job Satisfaction with Work Environment (subscale) | ||

| C. | I would like to change to another school if that were possible* | 0.644 |

| E. | I enjoy working at this school | 0.894 |

| G. | I would recommend this school as a good place to work | 0.836 |

| J. | All in all, I am satisfied with my job | 0.579 |

| Job Satisfaction with profession (subscale) | ||

| A. | The advantages of being a teacher clearly outweigh the disadvantages | 0.668 |

| B. | If I could decide again, I would still choose to work as a teacher. | 0.940 |

| D. | I regret that I decided to become a teacher* | 0.660 |

| F. | I wonder whether it would have been better to choose another profession* | 0.689 |

| * reverse coded questions |

Teacher Collaboration = Exchange and co-ordination among teachers + Professional collaboration in lessons among teachers.

| 33. | On average, how often do you do the following in this school?” Response options: “Never” (1), “Once a year or less” (2), “2–4 times a year” (3), “5–10 times a year” (4), “1–3 times a month” (5), “Once a week or more” (6) | Std.Factor Loading (Eng) |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange and co-ordination among teachers (subscale) | ||

| D. | Exchange or develop teaching materials with colleagues | 0.589 |

| E. | Discuss the learning development of specific students | 0.718 |

| F. | Work with other teachers in this school to ensure common standards in evaluations for assessing student progress | 0.671 |

| G. | Attend team conferences | 0.412 |

| Professional collaboration in lessons among teachers (subscale) | ||

| A. | Teach jointly as a team in the same class | 0.527 |

| B. | Provide feedback to other teachers about their practice | 0.53 |

| C. | Engage in joint activities across different classes and age groups (e.g. projects) | 0.618 |

| H. | Participate in collaborative professional learning | 0.414 |

Teacher Self-efficacy = Self-efficacy in classroom management + Self-efficacy in instruction + Self-efficacy in student engagement

| 34. | Self-efficacy in classroom management (subscale) In your teaching, to what extent can you do the following? Response options: “Not at all” (1), “To some extent” (2), “Quite a bit” (3), “A lot” (4). | Std.Factor Loading (Eng) |

|---|---|---|

| D. | Control disruptive behaviour in the classroom | 0.74 |

| F. | Make my expectations about student behaviour clear | 0.699 |

| H. | Get students to follow classroom rules | 0.869 |

| I. | Calm a student who is disruptive or noisy | 0.725 |

| Self-efficacy in instruction (subscale) | ||

| C. | Craft good questions for students | 0.544 |

| J. | Use a variety of assessment strategies | 0.681 |

| K. | Provide an alternative explanation, for example when students are confused | 0.725 |

| L. | Vary instructional strategies in my classroom | 0.727 |

| Self-efficacy in student engagement (subscale) | ||

| A. | Get students to believe they can do well in school work | 0.69 |

| B. | Help students value learning | 0.723 |

| E. | Motivate students who show low interest in school work | 0.758 |

| G. | Help students think critically | 0.653 |